We use Google Cloud Translation Services. Google requires we provide the following disclaimer relating to use of this service:

This service may contain translations powered by Google. Google disclaims all warranties related to the translations, expressed or implied, including any warranties of accuracy, reliability, and any implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, and noninfringement.

Highlights

- Khagendra Sangraula says, 'Being born, growing up playing with dust, growing up, getting married, giving birth to children, growing old, getting sick and dying - this was the circle of life within the narrow circle of geography during the mother's time.'

Those who know Khagendra Sangraula know that he also has another name – Kunsang Kaka. As for Sangraula, who is known by both names, it seems that even the same name of her mother was not in trend.

In the urban rush of Kathmandu, he thinks - 'Father's name was definitely needed in the children's vows, vows, weddings, Puranas, and sacrifices, but the mother's name was probably not needed. In the Tamsuk of such transactions, the name of the mother was not needed in the property ownership document.''

Then Khagendra feels that his mother's own body was not his. Mother was like a servant to all of us in the house. Khagendra says, "I am tired of work, I am deprived of money." His mother gave birth to 10 children – equal to children. Among them, the last daughter lived only 9 months. In the village of Khagendra, even Citamol and Jevanjal did not arrive in the name of Okhati, there were some traders who were superstitious about seeing planetary positions when they fell ill - astrologers who saw planetary positions, Dhami, Jhankri or Bijuwa who beat dhangra or plate.

Photos: Deepak KC/Kantipur

Photos: Deepak KC/Kantipur

'In such a situation, how could the mother save and raise us 9 children, I wonder,' Khagendra remembers the black and white days spent by the mother, 'Eight-ten years of the mother were spent carrying children in her womb. How many more years of mother's life passed by sucking milk, bathing, washing clothes, feeding-drinking and stroking children who were born one-and-a-half years apart.''

***

Khagendra Sangraula's book-'Avishrant Lakharlakhar' is the youngest book in 'Menu'. In a conversation with interviewer Uday Adhikari, before this book was published, a biography written on him by Ujjwal Prasai, 'Ek Baaghi', was published. Essayist, storyteller, novelist, columnist, analyst, translator, activist of civil movement, Sangraula has a wonderful aura in the Nepali literary world. He became known from abroad precisely because of his distinctive writing. And became a study addict. Originality in language-art is Sangraula's real invention.

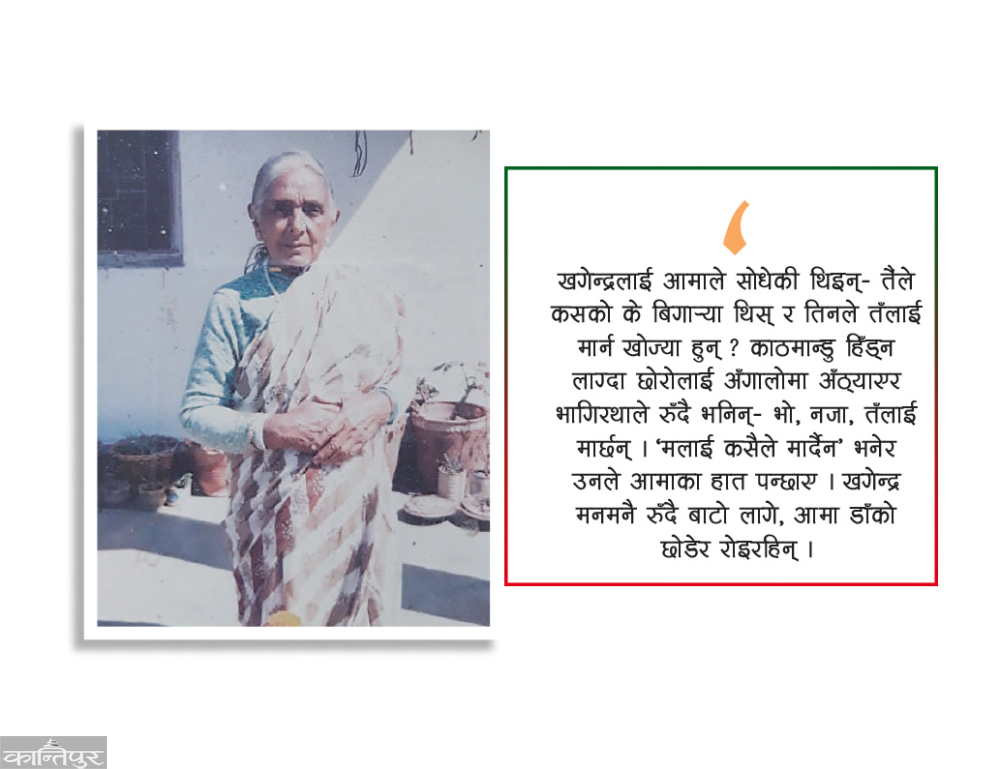

Khagendra Sangraula's mother Bhagiratha .

Khagendra Sangraula's mother Bhagiratha .

He is probably the most well-known and read Nepali contemporary writer. Hardly any other writer has received criticism and praise, criticism and praise here. Sangraula's 'In the rhythm of his own eyes', 'Samzhana quinettaru', 'Childhood footsteps' (memoir), 'Joonkiri's music' (novel), 'Kunsang kakaka katha' (anthology) are 'masterpieces'. Khagendra was born after three brothers. He had an older sister. Ten years after the birth of Khagendra, another younger son was born. Khagendra was full of pride – arrogant and arrogant too. Sharp in studies, he always stood first in his class. Later, mother used to say - now you are a bit of a caste, when you were little, you were careless! And pride is the same!

***

Khagendra's mother Bhagiratha Sangraula (1972–2054) was born in Yangpang, Taplejung. Bhagiratha's childhood was spent playing gatta with children, helping his mother with work, tending sheep and cattle with his brothers and sisters, looking for grass and firewood, watching the night dance played by his mother at the time of a man's wedding. Maiti Kharel of Bhagiratha was a man who had a right to do things in the village, was a doer, and was of the 'main' type. Khagendra has glimpses of his mother's house every now and then. Mamaghar was a two-day journey. That place was remote and isolated from our village. Houses were scattered far and wide. Mamaghar was at the top of the farm. There was a forest above the house, and a paddy field under the house," Khagendra recalls, "Rich uncles used to give me good dachina. Even with the greed of Dachina, I used to follow my mother to Mawal.' Paththa-pathhis who go to Mavali village to look for grass and firewood and look after the cattle used to play pipiri leaves, sing dohori and bring love. Casteism, untouchability, discrimination, harassment were strong in the village.

Khagendra heard Bhagiratha's description of her marriage to someone else one day, 'I was sixteen years old when I got married. Panchai baja ranwan was playing. They forced me on a dolly. I cried, sobbing. My mother also cried with me. They carried me on a dolly and kicked me. I saw darkness before my eyes. Fear said - where are you going to bring, what are you going to do? What will the groom's mood be like? What kind of mother-in-law is she? Who do I talk to? I felt as if I was going to have the same spasms when I walked towards the village of people I didn't know or didn't know. The people were all men. On the way, I felt sick. Which mouth should I say to whom? I opened my mouth when I finally finished eating. They let me go to the toilet to defecate. Uttaula Thetna kept teasing me by saying something along the way. In the end, they brought me into an unfamiliar house in an unfamiliar village.' Khagendra's father was Lakshmi Prasad Sangraula, an astrologer of his time. There was no culture of exchange of feelings or conversation at home. Lakshmi Prasad had a monopoly on speech - mother, children are silent listeners of father! Bhagiratha's voice was not heard except when he was doing ahranakhatan, when he was angry with his children about something and when he was singing a lullaby to the nanny. The silence of the house used to be broken - when the father reprimanded and reprimanded the children or recited the Gita during the Panchayan Puja or sat on the couch in the evening reciting verses from the Ramayana-Mahabharata or telling the news and stories of the neighborhood boys that he had brought from time to time to see astrology!

Khagendra heard Bhagiratha's description of her marriage to someone else one day, 'I was sixteen years old when I got married. Panchai baja ranwan was playing. They forced me on a dolly. I cried, sobbing. My mother also cried with me. They carried me on a dolly and kicked me. I saw darkness before my eyes. Fear said - where are you going to bring, what are you going to do? What will the groom's mood be like? What kind of mother-in-law is she? Who do I talk to? I felt as if I was going to have the same spasms when I walked towards the village of people I didn't know or didn't know. The people were all men. On the way, I felt sick. Which mouth should I say to whom? I opened my mouth when I finally finished eating. They let me go to the toilet to defecate. Uttaula Thetna kept teasing me by saying something along the way. In the end, they brought me into an unfamiliar house in an unfamiliar village.' Khagendra's father was Lakshmi Prasad Sangraula, an astrologer of his time. There was no culture of exchange of feelings or conversation at home. Lakshmi Prasad had a monopoly on speech - mother, children are silent listeners of father! Bhagiratha's voice was not heard except when he was doing ahranakhatan, when he was angry with his children about something and when he was singing a lullaby to the nanny. The silence of the house used to be broken - when the father reprimanded and reprimanded the children or recited the Gita during the Panchayan Puja or sat on the couch in the evening reciting verses from the Ramayana-Mahabharata or telling the news and stories of the neighborhood boys that he had brought from time to time to see astrology!

At that time, the wife was strictly forbidden to cut her husband's name . Don't say things you don't understand about your husband. Khagendra never heard father and mother say a double word. He never heard his mother say anything bad. They say, 'The silence of the parents is good according to the age of marriage.'

At that time, the wife was strictly forbidden to cut her husband's name . Don't say things you don't understand about your husband. Khagendra never heard father and mother say a double word. He never heard his mother say anything bad. They say, 'The silence of the parents is good according to the age of marriage.'

***

There was no market in Subang Gurungchap at that time. There was no custom of buying and selling. In Khagendra's memories, there was a market every fifteen to fifteen days on the hill in the forest above his house, there were not so many things that could be bought and sold. Grains, fruits and vegetables were grown in the fields. It was not customary to sell that thing. The old people used to say - selling vegetables makes me feel lazy. The leftovers would rot in the fields. Grain was sometimes bought and sold in small quantities. Khagendra heard that there was a market in Bijanbari, which was 4/5 days' journey from his house. His father and brother sometimes used to go to Bijanbari carrying tins of ghee. And after selling ghee, he used to go home and buy salt, oil, sugar, tea leaves, tobacco, cumin-pepper, clothes.

Poor women whose crops were not good used to come to Khagendra's house during famine. When her husband was not at home, Bhagiratha used to sell him some Pathi grain for free - Pathi's Ana-Sukama. She used to hide the money in a double-mouthed pouch. And she was very happy to give that money to her nieces and nephews during the festival. Khagendra remembers life in that village as 'uneventful'. They say, 'To be born, to grow up playing in the dust, to grow up, to get married, to have children, to grow old, to get sick and to die - that was the circle of life in the narrow circle of geography in the mother's time.'

***

***

of rural childhood Some parts keep changing like film reels in Khagendra's Smriti-Lok. He loved to go out and play. Bhagiratha used to urge Khagendra to carry his sister or to shake him in his lap. Kokra was upset when her sister didn't sleep. He stopped shaking the cock and tried to run outside. Bhagiratha used to abuse her by holding a lock of her hair and holding a rope of kokra in her hand. Actually, Bhagiratha was not so angry with her children. Khagendra remembers that his mother was angry only in a few incidents. In his stove, millet or corn was cooked, rice in a large pot, paddy rice in a small pot.

Bhagiratha used to give her children first dhindo and chikhla rice and a little paddy rice. Turukka used to pour milk on the paddy rice. Khagendra found the heap of corn not very sweet. I used to snort saying 'Don't eat junk food'. And his mother was angry with him. He used to add rice and milk. Bhagiratha used to get angry again saying 'How can I deliver?' Khagendra liked to study rather than work. Bhagiratha should not have told him 'read', but rather 'don't read'. Kerosene was rare and expensive in the village. Even after eating rice in the evening and going to sleep, he would light a kerosene bottle and read. Bhagiratha used to say to her, 'Sleep with the lamp off, the kerosene will perish'.

***

***

Bhagiratha's friends and colleagues were just work, work and work. Khagendra thinks - Where was his mother when she was free to walk, chat and laugh with her friends once? He didn't have time to get tired like this, to go to the funeral, to go to the bazaar, to listen to Puranas. During menstruation, three/days in a month were free from cooking. Khagendra's brother, who fasted instead of his mother, used to heat the stove and cook rice and tihun. His mother used to sit on the ground floor and keep repeating - rice so much, water so much, oil so much, salt so much!

Men did not break even in household chores. Men's noses were 'cut' while carrying water, cooking rice, washing dishes, mopping the floor, washing clothes. Mothers had to bear all the burden of labor. Bhagiratha, who was carrying the terrible burden of work, had no time to laugh. However, Khagendra remembers his mother smiling at some moments. While sucking milk, when the eyes of the child and the mother met, the mother smiled and smiled. When the child tries to move, stand, crawl, the mother laughs. "When the children spoke Toteboli, the mother used to be mad," he recalls. However, Khagendra does not remember his mother laughing loudly.

The first time I saw my mother crying was in the year 2007 - after Khagendra, Tribhuvan left the throne in Kathmandu and Rai-Limbu of Panchthar covered that opportunity and raised a 'movement'. "He doesn't like the fact that Bahun-Kshetri has seized his power and ruled over him. He has created an uproar to replace the opportunity." The Ba's took their swords and went up the hill to hide somewhere. We sat around mother on the stone above Devithan under the house to avoid children's movements. The men of Hulachal stormed our house with guns blazing, shouting and cheering. There was a rush of traffic. And we returned home,' Khagendra opens the old chest of memories.

That scene is fresh in his eyes - the pickled lopsi pickled in the barley was scattered all over the yard. The middle of the generation was cut in half in two or three places. The door was broken. Inside, the fireplace and the stove were bustling, the house was humming loudly. A pigeon with its leg amputated was lying in one corner of the barn. The mother took the pigeon in her hand, licked it, and ate it. At that sight, Bhagiratha clutched the pigeon to her chest and wept bitterly. Khagendra has written that memory of the year 2007 in 'Childhood Steps'.

One day, Bhagiratha Khagendra got angry with her elder brother Saila. Without looking, she hit her brother in the yard with a chirpat, the brother fell down. Then she splashed her brother with water. When her brother came to his senses, she hugged him and cried a lot.

Bhagiratha's youngest daughter was nine months old. She passed away on election day 2015. The memory of that moment in Khagendra's mind is like this, 'Mother and I are watching, first my sister's eyes got red, then my sister's breathing increased, and my sister's mouth became packed. And my sister died.' She was carrying her daughter in her arms, beating her chest, tearing her hair, and cried that day. The day her husband passed away, she fainted crying.

Bhagiratha's youngest daughter was nine months old. She passed away on election day 2015. The memory of that moment in Khagendra's mind is like this, 'Mother and I are watching, first my sister's eyes got red, then my sister's breathing increased, and my sister's mouth became packed. And my sister died.' She was carrying her daughter in her arms, beating her chest, tearing her hair, and cried that day. The day her husband passed away, she fainted crying.

***

052 year, on 1st of February, Maoists launched a rebellion by firing guns. Khagendra was arrested and disappeared by the authorities in Kathmandu. There was a great commotion outside, and he escaped under the pressure of the commotion. Khagendra heard - 'Bhagiratha is crying because her son has been killed.' And he rushed down to Jhapa. As a result, only bones are left by Peer - a hollow life, a sighing voice, tears in the eyes, and a slaughter on the cheeks! Mother's condition has become miserable. My mother squeezed my hands and said in a lost voice - Hey, are you? Anyone would have killed you. I was in love. Is this you? My heart was very sad when I saw that my mother was in that situation.'

At that time, Khagendra was asked by his mother - Dad! Who did you hurt and they tried to kill you? He could not explain - the story of autocratic power, rebellious rebellion and murder by power! When they were about to walk from Jhapa to Kathmandu, Khagendra's mother hugged her son and said, "Don't go, they will kill you." "No one will kill me," he said, pushing away his mother's hands. Khagendra went on his way crying, his mother left Danko and cried.

***

Khagendra's reading always seemed pointless to his mother. Seeing that he was studying late at night, his mother used to ask him, "Haven't you completed your examination yet?" In his understanding, 'reading' was meant to explain the test. She used to say - 'Oh, enough to read. Sleep now, your eyes will get worse.' After reading and working, Khagendra used to take clothes for his mother when he went to the village to meet him. His response was silent delight. When he left, he would put some money in his mother's hand, and mother would quietly take the money. Later, Khagendra found out that Bhagiratha kept saving that money without spending it. The next time she was going to leave, she would take the same money in her hand and ask him - do you have travel expenses?

Khagendra got the knowledge from his mother – tireless hard work, loving, thrift. According to Khagendra, the philosophy of being a mother is creativity, compassion, sacrifice, modesty, politeness, cooperation.

In Khagendra's opinion, the complaints of the mother who was 'deprived of speech' are immense, but they were never heard. Sometimes she used to sigh tiredly and say - 'Ah, my work'. "Sighs of a mother who was deprived of speech, rights and language were the painful expressions of unspoken grievances," says Khagendra.

***

In the memories of his mother, Khagendra Sangraula has only one feeling - regret, regret, regret again! Such is the regret-story. When he was 19 years old, Khagendra left home for Kathmandu - to study at the age of 22. Then he turned to the West in mastery and revolution. I didn't get a chance to stay close to my mother. Much later, his 82-year-old mother was brought to Kathmandu - sickly and exhausted with age and disease. His errant mother felt that someone should be by my side, someone should talk to me. But who has the leisure to sit next to her in the hustle and bustle of the city? Her mother cried uncontrollably when she was alone in the room. She probably thought, 'Everyone forgot me!'

At that time, the prime minister was Lokendra Bahadur Chand, a royalist, and the home minister was Jabajmargi Vamdev Gautam. Terrorism Bill was being introduced to level the terrorist. Khagendra became very busy - in the room discussion against the bill that took away civil rights, sometimes on the street. His wife was also busy - at home and at work. She used to be a little red mother who came with her mother, how can that child understand the old mother's attitude?

And Bhagiratha passed away in sorrow. Khagendra still feels that the brutal force did not allow me to be with my mother in the last moments of her life. If we could stay close, the restlessness and fear of the mother would be less and the death of the mother would be less painful. On a rainy day in June, Khagendra says, 'It is sad that I could not be close to my mother in those last moments.' It was a more difficult time.

difficult because her non-traditional Kazkiriya was not easily tolerated by her Hindu family. However, he stuck to his beliefs. He was teased not only by his family, but also by some of his friends who were called communists, but Khagendra Kiria did not stay. Later he wrote a book titled 'Aama and Yamdutharu', denouncing Hindu kazkiria and hypocrisy.

mother-memories sometimes surround; In the latter, his heart is always torn by the remorse of Kles, who is not able to stay with his mother.

प्रकाशित : श्रावण १, २०८१ ०९:४५

प्रकाशित : श्रावण १, २०८१ ०९:४५

२२.१२°C काठमाडौं

२२.१२°C काठमाडौं